FAIRBANKS — A quick look at the 1907 Tanana Directory leaves little doubt about what early Fairbanksans did in their spare time.

The business guide listed 59 bars in town, from Albright’s to the Wigwam Saloon.

The town’s population at the next census was listed at about 3,500 residents — one bar for every 60 people.

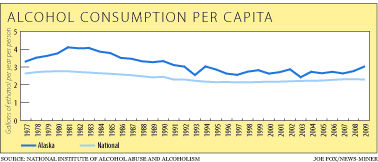

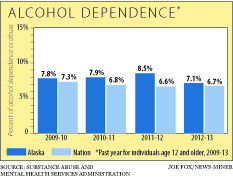

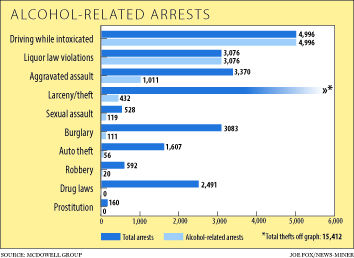

The numbers aren’t quite so striking today, but Alaska’s reputation for hard drinking — and the problems that come with it — remains. The state is among the U.S. leaders in per capita alcohol consumption, and a bevy of grim statistics, including high rates of violent crime, suicide and sexual abuse, have ties to the state’s struggles with beer, wine and booze. Alaska’s alcohol mortality rate is three times the national average.

“I think the problem has remained fairly persistent,” said Bernie Segal, who spent 30 years with the University of Alaska Anchorage Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies. “Drinking is part of the Last Frontier mythology among a segment of the population.”

But since Alaska’s early days, that drinking culture has been mirrored by efforts to limit its misuse, using approaches both conventional and unorthodox.

Prohibition laws were widely used — and often ignored — during the era of Russian ownership and territorial government. Influential Episcopal priest Hudson Stuck made it part of the church mission in turn-of-the-century Alaska to protect Alaska Natives from “low-down white men” plying them with booze.

Today, housing areas are set aside for residents with chronic alcoholism in hopes of giving them the stability needed to recover.

ol. The state is even sponsoring pregnancy tests in some bar bathrooms as part of an effort to fight Fetal Alcohol Syndrome.

But there are factors that make alcohol issues particularly challenging in Alaska. Many residents are transient, moving between communities or states before their problems can be addressed. The state is vast — and for the most part, sparsely populated — limiting the reach of many alcohol-treatment programs and regulations designed to curtail misuse.

The Fairbanks Daily News-Miner plans to spend the next year exploring the ongoing search for solutions to one of Alaska’s most vexing problems. The project will look at what has been tried, what may be working and what lies ahead in the fight against alcohol misuse.

A culture of drinking:

A steady succession of boom-bust cycles and male-dominated professions has contributed to impulsive attitudes toward alcohol in the state, said Mary Ehrlander, director of Northern Studies at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The professions that built the modern Alaska economy — fur-trading, gold mining, logging, fishing and oil — are often linked to men using booze as a remedy to isolation and boredom. Through trade and exploitation, those settlers spread alcohol to an Alaska Native culture that had no previous experience with it.

“We have a number of elements of this frontier lifestyle,” Ehrlander said. “It’s quite masculine, there are elements of risk-taking. For women, especially young women, there’s a culture of being able to hold your liquor and drink with the guys.”

But complicated feelings about alcohol always have persisted. Early fur-traders and whalers were notorious for exploiting indigenous Alaskans with liquor, which spurred laws that made it illegal to sell alcohol to Natives for nearly a century.

Through much of territorial history, prohibitions against any drinking were enacted, then widely flouted. Alaska District Judge James Wickersham’s diaries are filled with mentions of drunken mayhem and his struggles to combat it.

Alaska in 1899 became the first state or territory in America to mandate liquor licenses and also got a jump on the prohibition movement. Sixty-two percent of Alaskans voted in 1917 in favor of the “Bone Dry Law,” which urged Congress to ban alcohol in the state. The move occurred two years before the rest of the U.S. enacted prohibition.

Not surprisingly, given Alaska’s history, the vote contained some contradictions. There seems to be plenty of evidence that most residents kept right on imbibing, even after deciding their neighbors should stop.

“Alaskans did recognize we had a problem with alcohol, but I suspect that a lot of the people who voted to go dry didn’t intend to stop drinking themselves,” Ehrlander said. “They didn’t think they had a problem with alcohol — they thought others had a problem with alcohol.”

Easing the problem:

In some respects, Alaska still seems to take pride in its reputation as a bastion of booze-fueled good times. Even though alcohol misuse is linked to a variety of ills in the state, there is still a mystique surrounding heavy drinking in Alaska lore.

Anyone entering a tourist trap in Alaska coastal communities has encountered a common T-shirt slogan: “A small drinking village with a fishing problem.”

“Maybe we’re not all that unique compared to some communities across the U.S. and other places, but it really seems like part of our way of being,” said Katie Baldwin-Johnson, a program officer for the Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority.

Some state agencies and advocacy groups are exploring whether those attitudes can be changed.

The Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority is commissioning a comprehensive survey later this year to gauge public attitudes and knowledge about alcohol. With that data in hand, officials hope to be able to use it as a baseline to see whether public perception about alcohol misuse shifts alongside public education campaigns.

Baldwin-Johnson said there’s precedent for rapid societal shifts on public-health issues, citing declining acceptance of tobacco in the past decade.

A shift also may be beginning in the way alcohol misuse is perceived. Despite the obvious troubles of severe alcoholics — public intoxication, homelessness and crime among them — the issue is usually much more nuanced. Many of those who battle booze are professionals who have learned to mask their struggles, even as it causes underlying stress in their lives.

Baldwin-Johnson said often people affected by alcohol misuse don’t show many outward signs of a problem, but helping them find solutions must be part of the larger picture. Intervention efforts for that unseen group of misusers could be a key toward easing the problem, officials believe.

“The reality is, the rest of the iceberg you’re not seeing — and that iceberg is in the majority of the population,” she said.

Originally published July 30, 2015 by Jeff Richardson in Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.