FAIRBANKS — Mike Johnston looked toward the ceiling in his sparsely furnished room, made a quick mental calculation, then came up with a number.

He figures he’s gone to treatment for alcohol addiction eight times — maybe more — at locations in Fairbanks, Anchorage and Ketchikan. The 61-year-old Anchorage resident lives today at Karluk Manor, a nonprofit facility in Anchorage for severe alcoholics.

He’s battled booze for the past four decades, becoming a heavy drinker when he lived in Fairbanks during pipeline days. He’s been trying to sober up, on and off, ever since. Johnston said last week he’s been sober for three months, but he isn’t counting the days beyond that.

Such persistence may be a necessity for an Alaskan seeking help. People looking for alcohol and drug treatment in Alaska — particularly those using the subsidized public system — need to be prepared for a difficult, slow journey.

Social workers and clients have tales of long delays and daily calls to a facility, waiting for a bed to become available. They tell of alcohol-fueled trips to emergency rooms or jails while waiting for an opening at a detox or inpatient treatment center.

Such experiences defy the common view of substance-abuse treatment — an intervention, followed by a prompt trip to rehab. It can work that way for people with the resources to pay for private care or a trip to a Lower 48 facility. For those who use the public treatment system in Alaska, it’s more myth than reality.

“A lot of people have the perception that when you’ve hit bottom you call and say ‘Take me,’ and they’re ready for you,” said Joan Houlihan, the state’s behavioral health program manager. “Then they hit all these roadblocks.”

Through his many trips through treatment, Johnston said he’d sometimes seek help and be enrolled almost immediately. Other times he’d get put on a list, but his plans to sober up were usually derailed by the time he made it to the top of it.

“By then, I’m off chasing the ghost again,” Johnston said.

Social workers and addicts tell a similar tale when it comes to treatment in Alaska — the pieces are usually there, but accessing them can be an excruciating challenge.

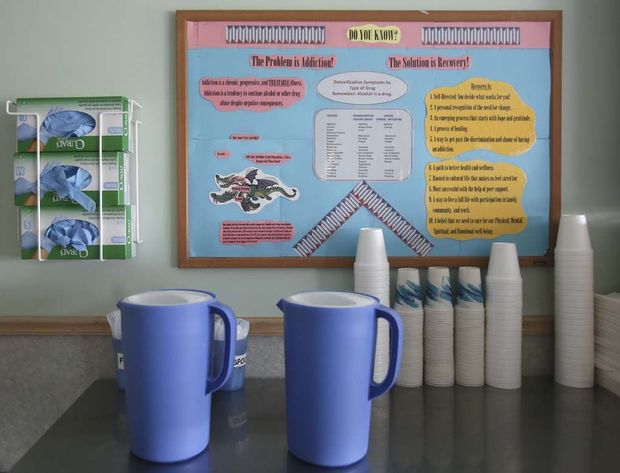

Substance-abuse professionals refer to the layers of treatment as a “continuum of care,” starting with steps as simple as early intervention education for people showing signs of a problem with alcohol. Patients may be subsequently steered toward varying stages of outpatient or inpatient services or even constant medical oversight if their problem is severe.

The process begins with a clinical assessment, which evaluates someone’s condition and what services are recommended.

The Ralph W. Perdue Center, a Fairbanks Native Association facility that treats Alaskans for alcohol and drug abuse, has a two-month waiting list to get an assessment. It’s not an uncommon delay, and it won’t be the first for most people using public avenues for treatment.

If the assessment determines there’s a need for medical detoxification, there likely will be another wait, particularly for those with drug problems. A bed at one of the 21 inpatient treatment facilities in Alaska — the step for many people who have a deeply ingrained alcohol problem — could take months longer.

Roy Naughton, a 37-year-old prison inmate from Kodiak, said he went on a long search for treatment before landing at the Perdue Center. Prison-based programs were filled, Naughton said, and the Perdue Center was the only facility outside the corrections system that would take his calls.

At Fairbanks’ Perdue Center, the largest substance-abuse treatment facility in the state, 120 people are on the “pre-waiting list” seeking some type of care. After that step, there’s a 40-person waiting list to get into the center itself.

“I had to really jump through hoops to get here,” Naughton said, shaking his shaved head at the thought while sitting in a conference room at the center on a mid-summer day. “It took three months of calling every day.”

Perry Ahsogeak, FNA’s behavioral health services division director, said he’ll work to squeeze in a potential client earlier at one of FNA’s substance-abuse facilities if they’re in a particularly critical stage of addiction. But, in general, waiting for services to become available in Alaska has become the norm.

Grace Jackson, a clinical associate at Anchorage Community Mental Health Services, said experiences like the one described by Naughton are pretty typical.

“To get one of those beds, you need to call every day,” she said. “Not your case manager — you need to call every day for like a month to get in there.”

Delays are also common for many of the state’s limited housing options.

At Karluk Manor in Anchorage, there’s a 75-person waiting list to get a room. The converted hotel uses the “Housing First” model for helping alcoholics, providing stable housing as a first step toward recovery. Tanana Chiefs Conference, which runs a similar facility in Fairbanks on South Cushman Street, reported a 300-person waiting list earlier this summer.

For Alaskans who live outside the state’s main population centers, treatment of any sort also may require a trip away from home. The reality of living in a huge state with a sparse population is that substance-abuse help isn’t available everywhere.

“If you live in Anchorage, Juneau, Fairbanks, you can probably get treatment,” said Alaska Deputy Corrections Commissioner Diane Casto, who was previously a longtime state behavioral health manager. “If you live anywhere else, you’ve got a problem.”

The delays for treatment aren’t necessarily an intrinsic part of the system, however, and Alaska’s recent history seems to provide some evidence.

Starting in the 1990s, a growing number of juveniles with mental-health and drug or alcohol problems in Alaska were being sent to the Lower 48 for treatment. There simply weren’t enough local options for Alaska kids, leading to a nearly 800 percent spike in out-of-state residential placements from 1998 to 2004.

That began to change about a decade ago, when the Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority and Alaska Department of Health and Social Services launched “Bring the Kids Home,” an effort to keep those juveniles closer to their families and communities.

Emphasizing the development of youth resources in Alaska has resulted in a huge shift, with a nearly 75 percent drop in placements to Lower 48 facilities from 2004 to 2011, according to data from the state health department.

Walter Majoros, the executive director for Juneau Youth Services, said his 42-bed facility almost always has spots available for new clients. He figures about 85 percent of the beds are typically filled.

In Fairbanks, the 10-bed Graf Rheeneerhaanjii Adolescent Treatment Facility, for Alaska Native youths ages 12 to 17, is also immediately open to new clients.

“I think we’ve gotten to a point where there are more beds than referrals,” Majoros said of the statewide system.

But expanding that sort of availability to adult programs is no easy step, particularly as funding sources flatten.

In fiscal 2005, public alcohol- and drug-abuse programs received $14.2 million in state funding and federal grants, an amount that climbed to $25.8 million by 2010. Today, those dollars look roughly the same, with $26.5 million budgeted in 2015 for such programs.

Not only would growth be expensive — a significant consideration as Alaska grapples with huge budget deficits — but it would also put a strain on the already thin supply of nurses in Alaska.

Houlihan, the state’s behavioral health program manager, said it’s hard to keep even Alaska’s existing facilities adequately staffed. A nursing shortage spans the health-care industry, which has made it tough to find nurses willing to work for relatively low pay at a detox center or other medically supervised facility.

Houlihan said state officials are aware of the shortage of options for alcohol treatment, particularly at detox centers, but have struggled to fill that void. When the Salvation Army closed a 15-bed facility in Anchorage a few years ago, the state got no response when it asked for proposals to add new detox beds, she said.

FNA director Ahsogeak said the thought of adding new start-up treatment facilities is daunting, both in terms of staffing and finances.

“Given that resources are limited, there’s not really the state money for someone who’s just getting started,” he said.

Such an expansion would also be a difficult sell to the public, said Karen Perdue, who served as the state’s health commissioner from 1994 to 2001.

The Ralph Perdue Center is named after her father, the first Fairbanks Native Association president, but she acknowledges the public is wary about pouring more money into social services like alcohol and drug treatment.

Public spending on substance abuse is tough to get “on the downstream” where it’s benefiting those who need help, she said. And after seeing many clients shift in and out of treatment numerous times, questions persist about whether the system is effective enough to be significantly expanded.

Perdue believes the Legislature’s reluctance to spend more money on the problem reflects that sentiment.

“It seems like a leap of faith to do that — a huge leap of faith,” she said.

An influx of money may be about to enter Alaska’s behavioral health system, even if it doesn’t come from the state.

A complicated brew of agencies and sources pays for health care in Alaska, including the Legislature, private insurers, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Indian Health Service. One of those sources, Medicaid, is scheduled on Tuesday to expand its eligibility for about 40,000 additional Alaskans.

That move, which was announced by Gov. Bill Walker in July, could provide motivation to create new facilities and services.

Majoros said Denali KidCare — an Alaska health insurance program for children — has been a big factor in the growth of the treatment system for juveniles. He’s seen many young clients shift out of treatment once they reach adult age, since the standards suddenly change at that stage.

“Once you turn 18, the rules change for income eligibility — they become a lot more stringent,” he said.

If many of those clients continue to be covered through Medicaid, it could fill a void, he said. Majoros believes those “transition-age youth” between the juvenile and adult systems are in an area ripe for expansion.

Ahsogeak, whose offerings through FNA cost $450 to $600 per day, said his organization likely will explore additional programs to coincide with possible Medicaid expansion. The Perdue Center plans to begin offering “tele-psychiatry” options for alcohol and drug treatment through the University of Colorado soon, he said.

Karen Perdue agrees Medicaid expansion will represent “a pretty dramatic change” for providers but said it remains uncertain specifically how it could affect Alaska’s health-care system.

“It’ll take a while to figure out what that means,” she said. “We may see a lot of providers step in to fill that gap.”

However, expansion is one of the developments that has added optimism in an area where it’s sometimes in short supply. Casto, who previously worked as the state’s prevention and early intervention manager, said she believes Alaska has made valuable gains in alcohol education in recent years and thinks there are reasons to look ahead with hope.

“This isn’t a doomsday prophecy,” she said. “We can tackle this problem if we see it as a shared responsibility.”

Contact staff writer Jeff Richardson at 459-7518. Follow him on Twitter: @FDNMbusiness. Reporting for the Daily News-Miner’s expanded coverage of efforts to reduce alcohol misuse in Alaska is supported financially by the Recover Alaska Media Project fund at the Alaska Community Foundation.

Originally published August 30, 2015 by Jeff Richardson in Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.