In 2008, the Australian government aired a television public service announcement in which a teenager who drank too much kills his own friend with a punch to the head. Another of the ads showed a teenage girl who got drunk at a party having sex on the lawn while dozens of her peers look on in judgmental amusement.

The Australian government invested millions of dollars per year in the ad campaign, designed to prevent underage drinking by scaring teenagers straight. The goal was a worthy one; reducing underage drinking helps reduce numerous negative societal and public health outcomes. But the real question is this: Does the technique work?

“All kinds of stuff has been done in the name of prevention, ‘Your brain on drugs’ and all that crap, that wasn’t based on evidence at all,” said Michael Koresky, an educator who was worked on youth substance abuse prevention for more than 30 years. “There’s not one iota of data that says Red Ribbon campaigns have any effect at all.”

Koresky is far from alone in this regard.

Diane Casto, the deputy commissioner of the Alaska Department of Corrections, a former state health official, agrees.

“One thing we have learned is scare tactics do not work with young people,” Casto said.

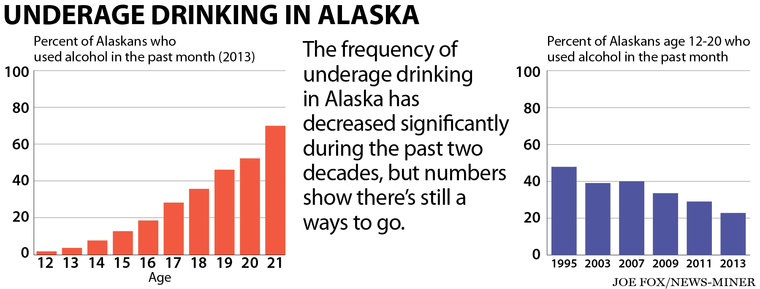

Alaska has made significant strides regarding youth alcohol misuse. Today, the state ranks near the bottom for rates of current youth drinking as well as youth binge drinking. Only Nebraska and Utah report lower rates of current use among youths, and only Hawaii and Utah rank lower in terms of binge drinking, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

At the same time experts celebrate this progress, they warn against thinking the problem is being solved.

“Communities must continue to build their prevention infrastructure and focus on sustaining their efforts and any resultant successes they’ve achieved,” said Claire Schleder with the Alaska Division of Behavioral Health. Although youth drinking rates in Alaska are lower today than in most states, it wasn’t always that way.

Building from a problem:

In the 1990s, Koresky was working for the Anchorage School District as its head of alcohol and substance abuse prevention.

At the time, high school students in Anchorage were binge drinking at a higher rate than students in other cities with comparable demographics, such as Seattle and San Diego. Anchorage students also reported consuming alcohol before the age of 13 at a higher rate than other cities.

Statewide, in 1995, just less than half of all high school students reported they had consumed alcohol in the last month, and 31 percent of them reported consuming five or more drinks in a row on at least one night in that same time frame.

These numbers aren’t dramatically different than the national average. In fact, in some cases they were slightly better, but the costs associated with them proved much worse than nationally. Heavy drinking and drug use are the leading factors causing increases in rape and sexual violence — areas where Alaska has historically struggled.

In 2005, underage drinking cost Alaska $316.5 million, according to estimates from the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. Underage drinking cost Alaska as much as $4,378 per underage person in the state, more than double the national average of $2,073.

Bringing hope to the city:

Koresky had found himself in underage substance abuse prevention after years of frustration working in treatment and intervention.

“(I) just got more and more frustrated trying to help these people, save these people, who are pretty far gone,” he said. “I want to go upstream and … keep them from falling in the river.”

Koresky thinks the solution to youth alcohol misuse isn’t prevention but something he says takes place at an even more basic level.

“We’ve found there’s a step before, or beyond, prevention that we call ‘youth development,’” Koresky said.

The Anchorage School District’s youth development model relies on the premise that youth alcohol misuse often comes about as a response to trauma or other risk factors. By working to mitigate trauma’s effects on kids, the youth development model seeks to stop the cycle of trauma and self-medication before it begins.

In the 1990s, while Koresky was trying to reduce the underage drinking rate in Anchorage, an organization called the Search Institute began looking at a trait they referred to as resiliency. They looked at people who had grown up in dysfunctional homes or with difficult childhoods, people who grew up surrounded by risk factors known to lead to alcohol misuse but who overcame these setbacks and thrived.

The organization eventually came up with a list of 40 developmental assets. The more of those assets a person had, the better their odds of overcoming difficulty to lead a healthy life, the institute reasoned.

At the time, Koresky and the Anchorage School District were putting hundreds of thousands of dollars into programs attempting to reduce problems such as suicide, teenage pregnancy and youth alcohol misuse but with little effect.

“It seemed like a no-brainer to us that we would put all of our money and time and energy into building assets for kids,” he said. “If we put all our money into prevention, into youth development, then not only does alcohol and drug abuse go down, but all the other bad behaviors that kids do go down if we do it well.”

About half the assets identified by the Search Institute are internal, personality traits like honesty and generosity, while the other half are external, “like teachers who are friendly and parents who are concerned, people who believe in them and a community that values them,” Koresky said.

When the Anchorage School District adopted the developmental asset approach in 1996, its students “were much worse on almost every measure when it comes to alcohol and drug abuse,” Koresky said, citing information from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Today, after 17 years with the program, Anchorage students are less likely to binge drink than their peers nationally and less than half as likely to binge drink as their peers from 1996. This transformation cannot be directly linked to a single program like the one undertaken by the Anchorage School District, but research has shown the asset building like that done in Anchorage schools has a positive impact on underage drinking and the risk factors that often lead to it.

At the same time the Anchorage School District was working on developmental assets in an urban setting, a similar approach was being developed in rural Alaska.

The People Awakening:

In the mid-1990s, while conversations were focused on the problem and prevalence of alcoholism in rural Alaska, a group of Alaska Native elders and University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers teamed up to begin studying and implementing solutions.

This led to the eventual creation a project called The People Awakening, through which UAF researchers Gerald Mohatt, Stacey Rasmus, Jim Allen and others began working with people who had successfully overcome alcoholism and those who had successfully avoided it their whole lives. Their goal was to identify what factors had helped these people succeed where so many others were failing.

Through this work, they developed a concept they called “protective factors” — something remarkably similar to the Search Institute’s developmental assets.

“A real subtle difference from this approach to prevention is it’s not about risk factor reduction, it’s instead about growing protective factors,” said Allen, now with the University of Minnesota. “The beauty and strength of that is protection is not the opposite of risk. It mediates risk. Trauma can happen, but how your family and your community and your support system responds to trauma has a lot to do with whether the young person will weather that experience and grow up to a life of promise.”

To build those protective factors at a community-wide level, the researchers and rural leaders behind The People Awakening began another program: Qungasvik. Like Koresky and others in the Anchorage School District, Qungasvik leaders attempt to engage not only young people but also the family members and adults who can influence them.

In their research for The People Awakening project, the UAF researchers identified four categories of protective factors among the Yup’ik people who participated in their study that helped lead to alcohol abstinence or non-problem drinking.

Those four categories were “Things I want for myself,” “Things I want for my family,” “Things I want for my body/well-being” and “Things I want for our way of life.”

Taking those categories and creating strategies for building them is where Qungasvik comes into the picture. The program’s efforts focus on connecting the youths of a rural community to the adults in a meaningful way.

“That was what could help support what the community was already doing. They were naturally already talking this way,” Rasmus said. “The first thing they said was we don’t want just another suicide prevention or another alcohol prevention — we want to be focused on wellness.”

At the moment, Rasmus and Allen are attempting to take the data they’ve gathered from their years working with western Alaska communities to establish Qungasvik as an evidence-based solution for not only alcohol misuse but also for other issues facing rural Alaska, such as suicide.

The right direction:

Today, high school students in Alaska are significantly less likely to drink than their peers from the 1990s. In 2013, the most recent year data from the youth risk behavior survey is available, 24 percent of Alaska high school students reported having a drink in the past month — just more than half of the 47 percent of Alaska students who answered the same question in 1995.

In 2013, 12 percent of Alaska high school students reported having five or more drinks in a row — just more than one-third of the 33 percent of Alaska students who answered the same question in 1995.

Similarly, the number of Alaska high school students who reported having their first drink before turning 13 fell from 39 percent in 1995 to 15 percent in 2013.

Protective asset-building is far from the only measure being used to prevent underage drinking. Many evidence-based programs are being implemented throughout the country. Where the asset-building method sets itself apart, though, is through its success not just treating a single problem like underage drinking but instead empowering youth to avoid underage drinking and the numerous negative outcomes that come along with it.

Several school districts, including Fairbanks, continue to use campaigns like Red Ribbon to spread awareness of drug and alcohol misuse. These days, however, Red Ribbon is used less as a way to scare kids straight and more as a catch-all substance abuse awareness method, according to Montean Jackson, the Fairbanks School District’s director of prevention and intervention programs.

Along with asset building, health experts and educators are also working to strengthen awareness and outreach efforts. In May, the Alaska Wellness Coalition began an awareness program called Be [You] Alaska.

The program uses data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey to show high schoolers in Alaska that most of their peers don’t drink. The campaign mixes the data from the survey with anecdotal stories of youth from all around Alaska who are living and having fun without drinking.

It hopes to build upon the efforts already underway in the state by reinforcing the idea that it’s not just healthy to abstain from alcohol, it’s normal.

Koresky admits there’s no way to directly link specific efforts to city- and statewide reductions, but the SEARCH Institute research says the people with the greatest potential to build assets for kids are the parents and teachers who serve as their instructors and role models.

“Part (of the increase) is just norms,” Koresky said. But beyond that, he said, the biggest improvements for Alaska’s students in the last two decades have come from growth of protective assets. And that change, Rasmus and Allen said, can only take place with the help of the entire community.

“If we want to reduce alcohol consequences, the community’s going to have to change,” Rasmus said, “and that’s what this process really does.”

Originally published November 4, 2015 by Weston Morrow in Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.